Making sense of lost savings: Takeaways from the DOE's Commercial Energy Code Field Study

Building energy codes have a 40-year history of reducing consumer energy bills—but good execution can make a big difference in yielding their full potential.

A 2016 Department of Energy (DOE) study found that lacking code compliance in multiple regions left a lot of savings on the table: an average of $189 per thousand square feet, simply due to design and construction practices not meeting basic energy code requirements.

In 2018, Slipstream led a commercial new construction baseline study in Minnesota. The project team assessed the lost energy savings potential of 78 buildings spanning multiple commercial sectors, reporting an overall statewide potential of $10 million in annual lost energy cost savings.

As energy codes seek progressively deeper savings, they've become more complicated. Slipstream partnered with Cyclone Energy Group and PNNL on a new study led by the Institute for Market Transformation (IMT) to investigate this complexity, targeting buildings with complex heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) systems (i.e. variable air volume (VAV) systems, water-source heat pump systems, etc.) controlled via a building automation system. Funded by DOE, the study looked at lost opportunities for energy cost savings in 50 buildings comprising office, education, and high-rise multifamily applications.

Study objectives

There are many studies that seek to understand how design professionals and builders meet (or don't meet) codes. Where this study differs is its specific focus on complex HVAC and lighting control elements required by the energy code. Due to their complexity, these control elements can pose multiple challenges during the design, construction, and operation phases of a building, complicating proper implementation. This difficulty is further heightened by limited awareness or understanding of the energy code's intent.

Identifying deficiencies in code compliance can support code writers, building code officials, and the design and construction industry in recognizing areas for improvement that will ultimately enhance energy efficiency and benefit building owners.

Other goals of the study include:

- Benchmarking current practices in design and construction of complex control systems

- Validating impacts of energy code elements and other energy efficiency initiatives

What we found

There were three main components of this study:

- Building recruitment

- Drawing reviews, where we looked for complex HVAC and lighting control elements in the building's design documents

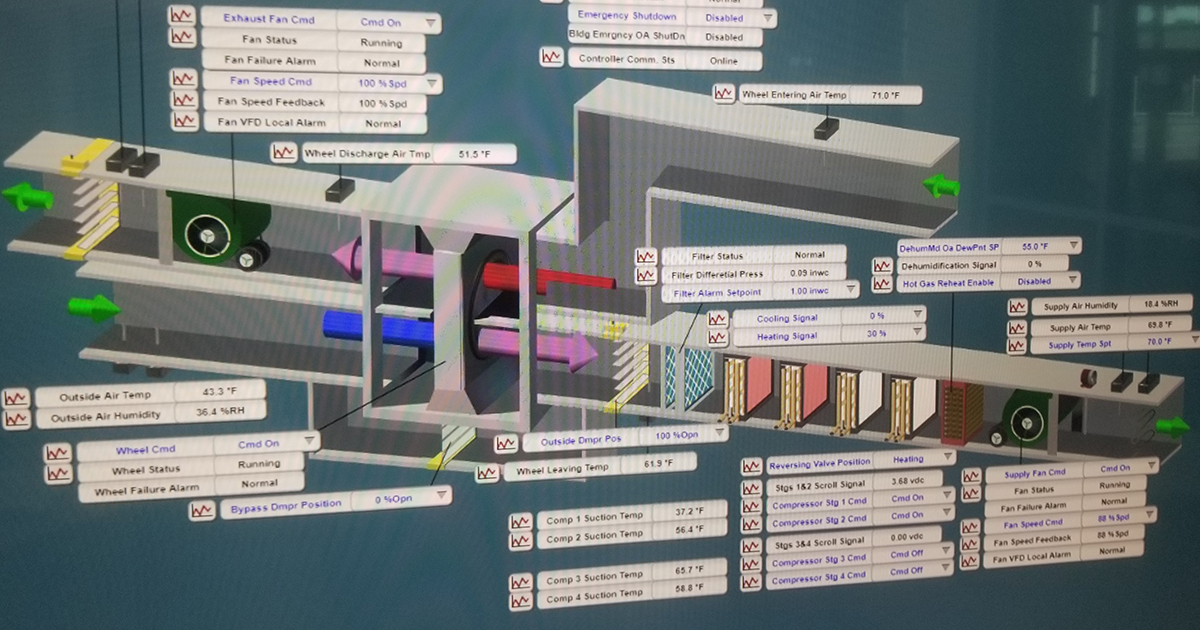

- Site visits at early occupancy, where we documented how these elements of the code were implemented. To get an accurate read of the HVAC and lighting controls in typical operation, these site visits necessitated a deep dive into each building's automation system (BAS).

This two-part approach of data collection allowed us to understand how these code elements were being handled in the design, construction, and operation phases of the building lifecycle. And with that data, we were able to analyze the annual lost savings per unit of floor area, and target the most significant lost energy cost savings.

We found that office and education had higher average annual lost savings per square foot than multifamily, largely due to the more complex control code elements in office and education building HVAC. Office and education facilities often rely on VAV systems as their primary HVAC solution, thereby triggering code requirements that are more complex to navigate and apply. Additionally, nighttime shutdown requirements are not applicable to multifamily, as they are occupied 24/7.

Building Type |

Average annual lost savings (per 1,000 ft2) |

|---|---|

Office (17 buildings) |

$195 |

Education (12 buildings) |

$221 |

Multifamily (21 buildings) |

$72 |

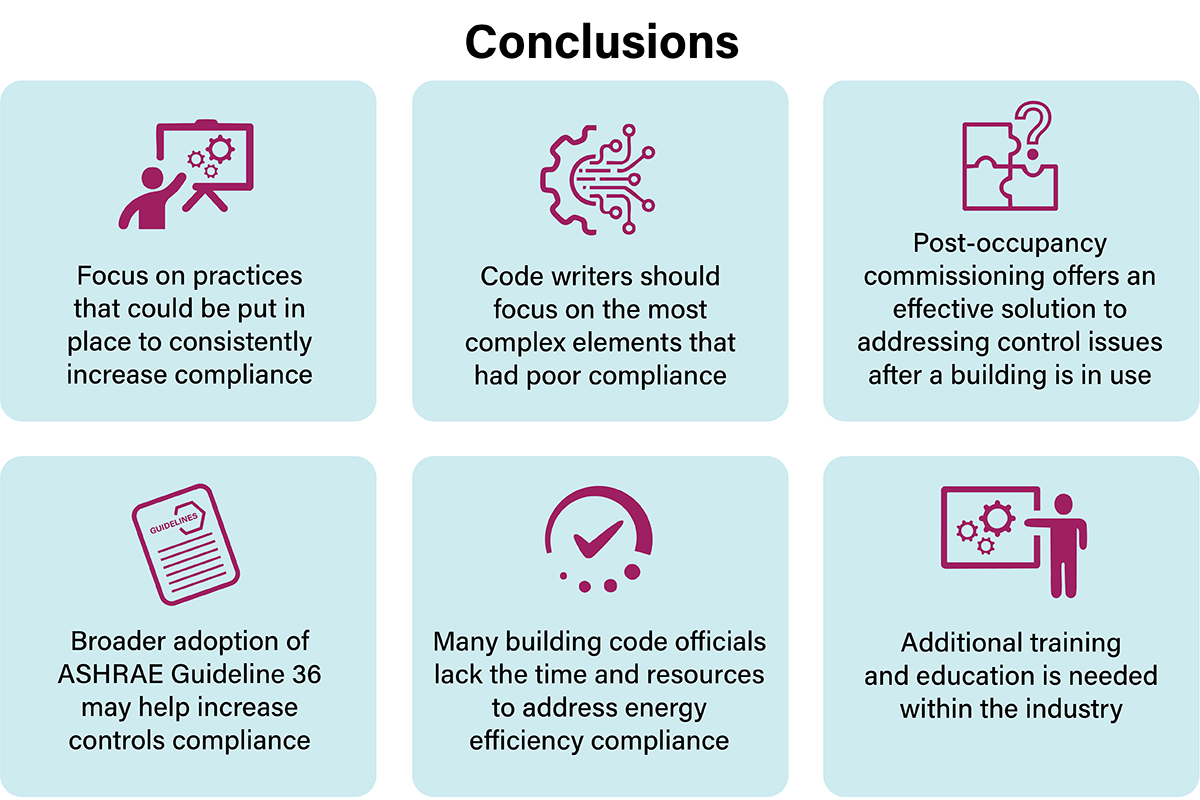

When comparing all the buildings in the sample, there is a large range between the least and the most lost savings per square foot. This wide variance in compliance across buildings indicates that achieving compliance is feasible; the codes community (code writers, building code officials, the design and construction industry) should focus on supportive practices that could be put in place to consistently increase compliance.

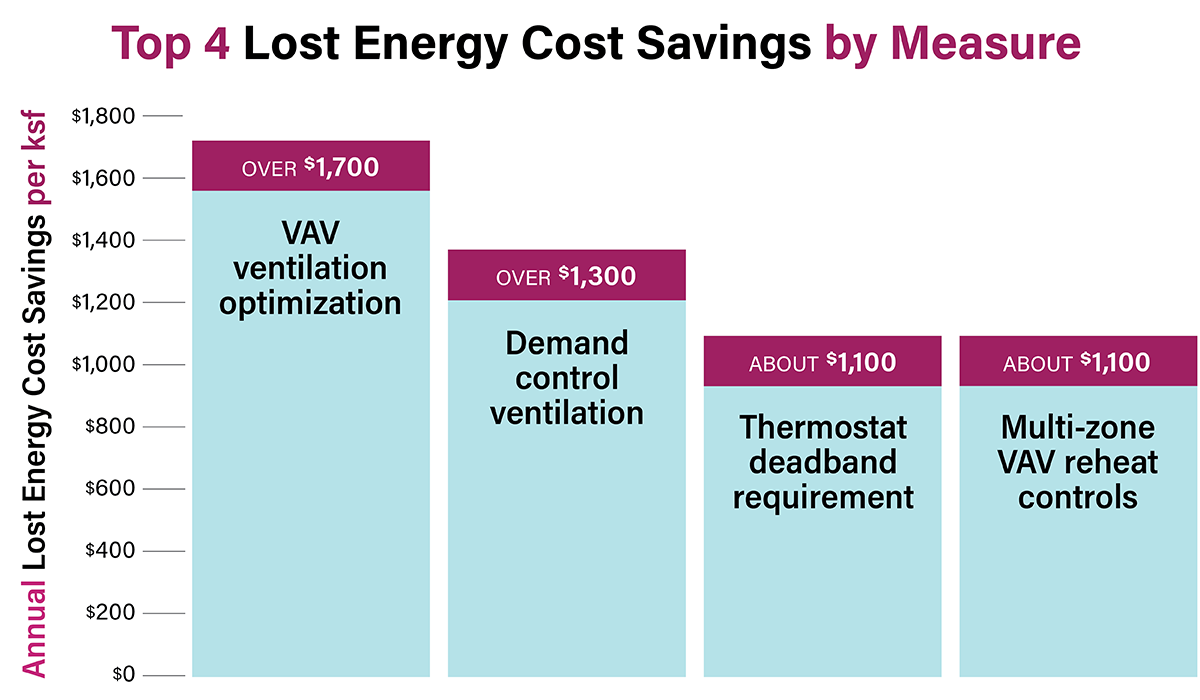

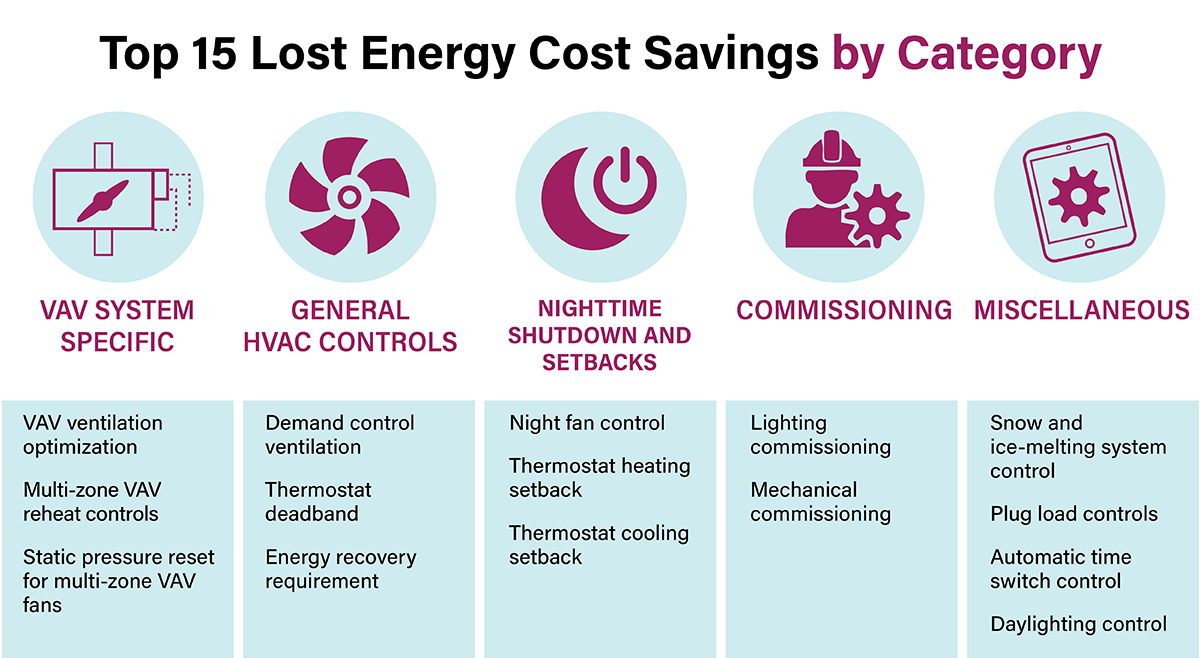

The top 15 measures for highest lost energy cost savings per unit of floor area reflect how complexity is tied to compliance. These elements have high energy impacts and are either frequently observed to not meet code or are new additions to the latest code version. They are often overlooked during design (leading to issues that persist through building construction and possibly through operational life) or mis-programmed in the BAS after occupancy (despite initial code compliance in design). Possible reasons include limited awareness of the requirements, past negative experiences, perceived risk, or weak quality control.

Interestingly, none of the sites involved in the study fully met the energy code requirements for HVAC and lighting controls. Even buildings constructed by sustainability-focused companies missed some requirements of the energy codes in the design documents or in the implementation process. This finding caught our attention, as it suggests there's at least some room for improvement everywhere.

Given these insights, we questioned what steps we could take to ensure future buildings consistently meet code.

Key takeaways and recommendations

Keep it simple, when possible

Code writers play a huge role in code advancement; one path forward suggested by this study is to continue simplifying the most complex elements of the energy code (i.e. those with high lost savings). Code writers could also consider the addition of new simpler measures for future code updates where possible. An example of this approach is the introduction of new code requirements for lighting task tuning. This measure is typically low-cost, widely familiar to most lighting contractors, and generally easy for the design and construction community to understand and implement.

Post-occupancy commissioning

Post-occupancy commissioning offers another important way to address deficiencies in complex control issues after a building is in operation. We found that commissioning requirements were often not fully followed; this one strategy could improve compliance of many other measures too. Even when code-required commissioning is completed at the end of construction, HVAC and lighting control systems can still deviate from their originally intended sequences once the building is occupied. Conducting commissioning post-occupancy ensures that any deficiencies are corrected and that systems function as designed, even after tenants have moved in.

Promote adoption of ASHRAE Guideline 36

Another possible solution to increase code compliance with HVAC controls would be to promote broader adoption of tools such as ASHRAE Guideline 36, which was created to guide building designers and operators to maintain best-in-class HVAC sequences. A field demonstration of ASHRAE Guideline 36 in California demonstrated the cost effectiveness and energy savings potential of installing optimized control sequences in existing commercial buildings, achieving 11–17% electricity savings with a 2–7-year simple payback for updating software in buildings that already had modern control systems.

Utilizing BAS packages pre-configured to comply with ASHRAE Guideline 36, along with adequate training for controls contractors, could significantly improve controls programming and commissioning. These pre-configured control program libraries can be readily applied without too much customization or modification in the field and are easier to apply for new construction than retrofit buildings.

Work in tandem with Building Performance Standards

Building Performance Standards (BPS) for large buildings, now adopted by several states and jurisdictions, help ensure buildings are continuously monitored, maintained and optimized for lower energy use and carbon emissions. If a new building is expected to comply with a BPS, the building team should be more likely to pay attention to energy impacts of controls and/or assess deficiencies. By introducing progressively more stringent standards for existing building energy use, these standards elevate the importance of effective controls.

Use resources developed by industry groups and allies

To support the adoption, implementation, and enforcement of Automatic Receptacle Controls (aka plug load controls), a NEMA task force, in collaboration with the DOE Plug & Process Load group, has developed guidance materials and downloadable resources addressing application design, end-user operation, and value proposition of plug load controls. These resources can be found here.

Increase training of complex codes

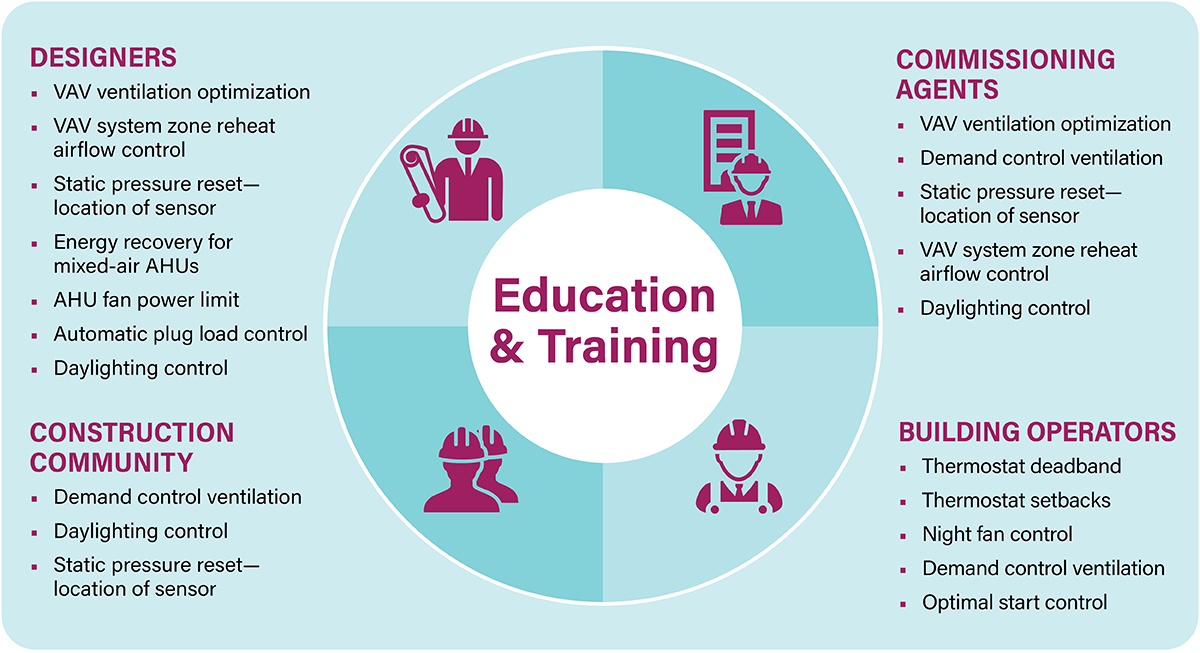

Bridging the knowledge gap with training, circuit riders, and code support programs focusing on these complex elements (and understanding their underlying intent) promotes a smoother adoption of new practices and approaches to increase code compliance. Most of the top lost savings measures can be addressed by integrating better codes training in activities throughout the industry. Depending on whether it's a design, construction or operation issue, we can target different audiences for training and intervention and develop specific recommendations. The code elements outlined below represent those most commonly overlooked, organized by the role within the codes community that has the greatest influence over each measure. Providing targeted training for each role in their areas of highest impact could help strengthen compliance consistency and support better building performance.

We believe the results of this study can be used to improve design and construction trends, as well as address the knowledge gaps through trainings, interventions, and future code updates.

To learn more about this study and our findings from it, you can watch the full webinar here.

This project was made possible by a grant awarded by the US Department of Energy's Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy Building Technologies Office and based upon work supported by the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy (EERE) Building Technologies Office (BTO) under the Commercial Energy Code Field Study: Targeting Large Complex Buildings project, Award Number DE-EE0009078.

The views expressed here do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Department of Energy or the United States Government.