How well do cities include the community in their action plans?

Laura Helmke-Long is part of a team of researchers at Indiana University who recently published an article in Climate Policy.

The article looks at how states and municipalities incorporate certain considerations into climate action plans or other plans with climate-related components like sustainability and energy, as well as comprehensive plans that feature sections on these topics.

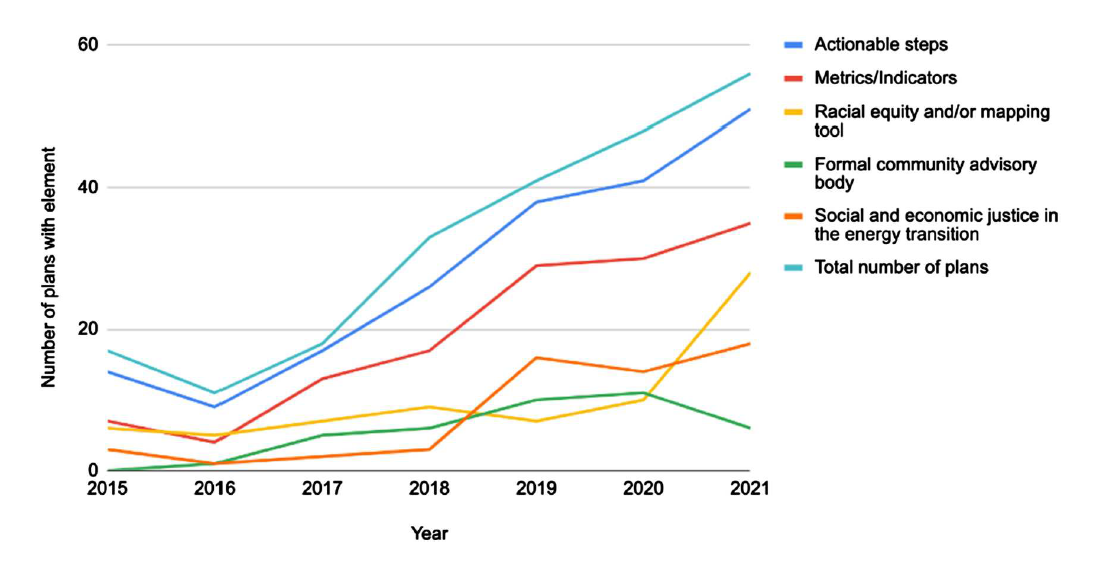

For the Climate Policy article, Laura and her co-authors reviewed state and municipal planning documents to see how much—and how meaningfully—their plans addressed the potential disparities of who bears the costs of and who benefits most from climate actions. The article finds that while state and local governments have paid greater attention to these issues in climate policy over time, especially in recent years, there are elements that still need further development to promote meaningful engagement with the community. For example, only a few plans include a "formal community advisory body"—a tool the team identifies as a crucial measure to include community input, engagement, and outreach in the planning process.

Laura is currently pursuing her PhD at the Paul H. O'Neill School of Public and Environmental Affairs at Indiana University. That's on top of her role as a policy analyst here at Slipstream.

We spoke with Laura about the Climate Policy article, her broader research, and the ways that nonprofit organizations like Slipstream can help cities build their capacity to engage with communities. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Zack: Tell us about your background. What was your path to getting a PhD, and how did you end up here at Slipstream?

Laura: I went to undergrad at UNC Chapel Hill. After college I worked for the Chicago Public Schools in their administration, taught high school Spanish for a year, traveled and lived overseas, and then returned to the US to do a policy degree getting my Master's in Public Affairs. After that, I moved to DC and worked at the EPA's ENERGY STAR Program, got sidetracked in my career by living in Europe for almost a decade for my husband's job, which was fun—

Europe! I'm jealous of this background.

It was fun! But then I came back to do the PhD at IU, where I'd gotten my Master's prior to starting the job at the EPA.

So I've worked for government or in academia until working at Slipstream. This is my first time in the nonprofit sector.

I want to hear about your role here at Slipstream, but first, let's talk about your academic work. What are you looking at in your research?

In my dissertation, I try to understand how cities see the vulnerabilities in their communities and whether they're looking at those vulnerabilities and trying to address them—especially in relation to climate change, the energy transition, and energy burdens.

That's helpful to understanding why they're doing the things they're doing and then seeing what factors seem to motivate and lead to greater success in certain places versus others.

Do you have a common measure you've identified so far as leading to success?

Well, part of the problem [with trying to assess success] is that these are insights on process rather than actions. A lot of this stuff has to do with the fact that I'm studying planning documents, which are aspirational in nature. It doesn't mean they're going to do the things in those plans, but it sets, you know, the path forward.

So you've got these intentions and the outcomes that might happen because of what they do—or don't do—from their plans, and those effects can take a long time to see if there are any positive outcomes. It's hard to say definitively, "Oh, this measure works and here are the benefits."

I think we probably could see—I'm not studying this specifically, but I would expect—that school districts that adopt electric buses see a reduction in some asthma and respiratory illnesses in kids. I think that data could be coming out soon, but I'm not in a public health school to study that.

But these planning documents give you insights into that process?

Yes. What I'm looking at in my dissertation research is how cities engage the community in the planning process. And then I'm going to be following up to see how they are continuing to engage with the community. Do we get the people in there? Is it just the usual players?

You know, a lot of times in the planning process, it's just older retirees who have the time to attend the meetings and go to the planning sessions.

That's something I notice just as a concerned citizen, especially in a city like Chicago, where a lot of decisions are made in public hearings that are at 9 a.m. on a Tuesday or whatever.

Right! But now a lot more places are providing incentives or helping support people in the places where they're living, providing child care, providing more services and in other languages, sometimes providing food to get more people to come and give their voice to the planning process.

And then I'm looking at: Does having this voice in the planning process actually affect the content and the plans in any way? Are they then thinking about things that they might otherwise overlook from the concerns people bring to the table? And finally, are they then incorporating those concerns into their final plans?

A chart from Helmke-Long et al.'s article that follows the progress in the way plans have incorporated metrics, actionable steps, and other elements. While the use of metrics has increased over time, concepts such as a formal community advisory body have lagged behind other elements such as mapping tools.

How well are cities, generally, working with the community?

What I'm finding in my research is that sometimes bigger cities, instead of doing a broad campaign to inform or get input from their community, they're more selective with stakeholders. The city will say, "We want someone that's worked with community organizations, but we're not going to work with the organizations themselves." They don't want to make it a free-for-all. Though, to be fair, I'm still working on analyzing the data and I'm not sure if this is really a trend.

But, you know, with that approach, who ends up excluded and who's included? Is it really easier to make progress when you don't have hundreds of voices? How much harder is it, really, to sift through that information and make sense of it?

So that's part what I'm trying to understand as a researcher.

For a journal article, are you making an argument, or just reporting on your research?

[The piece that was just published is] more of a descriptive piece, talking about trends in planning processes. Other people's articles have studied climate plans. Some scholars have studied sustainability plans, some energy plans. We took a wide net to look at all types of plans where climate and energy and sustainability might be discussed. And we also included comprehensive plans, because sometimes smaller cities don't have the capacity to do a separate climate plan or sustainability plan, but they might be addressing these concerns in a comprehensive plan.

We also cast a wider net. Many articles seem to have focused on, say, all the cities in one state. Others have focused on the 100 largest in the US. We—and again, this isn't capturing everything—picked the five largest cities in every state.

Why's that?

A lot of states don't have any cities even getting into the Top 100 in the country. But there are things happening in states and cities all across the U.S., even in places you might not expect. Plenty of places are very forward-thinking on these issues.

And a lot of small cities are doing cool things, even though they have less capacity.

What trends have you seen from this study?

I think it shows that there are positive trends. Our study doesn't differentiate between someone who does one small thing and someone who has done a hundred things. Sometimes these things might be small in comparison to other places doing more. So this is not saying that everyone is doing a lot, but that several places are doing something.

It's important to remember that in this academic research, we're trying to describe what's happening and lay the groundwork for future research and give a snapshot of where things are at, and do it in a rigorous, empirical way. We need to make sure we are following a protocol and not just, you know, interpreting it through one lens.

I saw that my hometown of Rochester, New York was in there! Though I suppose it's one of the five largest cities in New York.

Oh, really? While I don't remember what we specifically noted them doing, I'd say we didn't highlight anyone that wasn't doing something interesting. We were pulling out things that were notable.

[Editor's Note: In 2019 the City of Rochester unveiled Rochester 2034, a 15-year comprehensive plan covering a wide range of topics to position the city for economic growth.

In the paper, Laura and her co-authors highlighted that the city's plan included mention of the more than 3,400 climate refugees that settled in Rochester following Hurricane Maria. According to the paper, "The plan put forth several strategies to provide services for refugees and integrate them into the community and called for an analysis on potential population changes from climate refugees."]

Is this a relatively new approach? To cities, I mean—seeing community engagement as a priority.

I don't know if community engagement is new. A lot of the EPA regulations used to require public comments and things like this.

What I think is new is trying to cast a wider net, being more reflective and purposeful and trying to capture more voices, versus how it used to be just, like, "Okay, we're holding this hearing. You come to us. If you're not there, no big deal."

What are the benefits of this newer approach—of casting a wider net?

I think it's important for cities to show that they're not just checking boxes. They can show people that they really do value their voices. As we've seen in recent years, there's a lot of distrust of government, but I think, especially at the local and state levels, this is a place where you can build up some trust.

As a practitioner, how are you seeing your work at Slipstream help cities achieve their plans?

I think what's important is Slipstream, at least in the roles I've played here or seen others do, is in helping build up or complement local governments' capacities. For example, we have helped local governments in Wisconsin on navigating federal funding opportunities and we have provided resources to communities or organizations that might have less resources to work with—say, for federal grant writing. We have helped cities like Chicago model the impacts of electrification on energy bills and supported Green Bay with their climate action plan.

We've helped them understand some of the funding coming out from the federal level and all of those pieces. And interpreting some of the policy for them helps build up capacity in these organizations.

Likewise, is there anything you've learned here at Slipstream that informs your research?

Oh, there's a ton. I feel like I learn more working here than reading stuff. Just understanding that this work takes time. It's messy. There are constraints, you know—changes in administrations can change policies, but that there's still so many people doing so much good work.

I think as a scholar, you're not quite aware of what happens in the private sector. I'm reading what cities are doing and, you know, they'll mention that they got support from organizations like Slipstream or other groups and it's hard for a researcher to see exactly what that role is.

I think if I were to do more research, I'd look at that interplay of the nonprofit sector and public entities and how they move forward together, because that's been really interesting being in it now.

That doesn't come up in policy school?

It does! [Laughs] It's just that my research is focused specifically on the local government players.

Laura's article can be found in the December 2024 issue of Climate Policy. Her co-authors include Alana Davicino and Colin Murphy, also of the Paul H. O'Neil School of Public and Environmental Affairs at IU, and Sanya Carley of the Kleinman Center for Energy Policy at the University of Pennsylvania.