A simple timer reduced energy consumption in a military facility by 34,000 kWh annually

Sometimes the simplest things can have the greatest impact when saving energy in commercial buildings. The key is to identify those opportunities. Slipstream worked for several years with Belkin International and Lawrence Berkeley National Lab in a Department of Defense sponsored study to evaluate a Belkin technology designed to identify and quantify specific electric loads operating at any given time. The system works by applying machine learning algorithms to measurements made where electrical service enters a building. This approach to load identification could potentially offer benefits compared to methods that require more measurement hardware and/or use less sophisticated algorithms.

The team worked in three buildings at Joint Base Lewis McChord (JBLM), a large Army and Air Force base near Tacoma, Washington. The buildings included an office-type facility for IT work, a barracks building, and a vehicle maintenance facility.

Slipstream’s main role was to collect circuit-level electric power data at the facilities, data that was used to “train” the machine learning algorithms in the Belkin system. Dan Cautley, Slipstream senior engineer, led the effort, and worked with a local electrical contractor to set up and maintain measurement of one-second resolution power consumption on 306 electric circuits for periods of 4 to 14 months.

Slipstream also worked to identify and implement energy efficiency opportunities – intended to provide concrete evidence of the value of the electric power itemization. While the itemization technology proved only modestly successful, one specific efficiency demonstration project in the third building investigated jumped out as a winner.

The vehicle maintenance facility is a 33,000 square foot facility consisting of shop areas with 14 vehicle repair bays, plus an office wing. A number of pieces of industrial-scale equipment stood out as potentially high energy users, in particular two compressors and a pair of overhead gantry cranes, each of which used 277V, three-phase motors. The team thought these systems might provide examples of large motor-based loads that would be identifiable and would offer efficiency opportunities.

It turned out that those loads were operated infrequently – the total energy consumption of compressors and cranes was less than one percent of the building’s total. But the team discovered much higher energy use in another system. This was a vehicle exhaust extraction ventilation system, a fan connected to flexible tubes in each work bay, intended to remove exhaust fumes from vehicles when their engines are operated inside the facility. Slipstream data showed the system was operating continuously from the time monitoring was started, at an average power of 3.9 kW (16 percent of facility total). Given that work on operating vehicles was infrequent, most of this operating time was clearly unnecessary.

After conversations with JBLM Department of Public Works staff, Slipstream received approval to move forward with a retrofit, and worked with a local contractor to install a simple manual switch that signals the facility’s direct digital control system to operate the fan for a period of two hours each time it’s activated. System operation is important for controlling exposure to exhaust fumes - staff training by the facility’s operational manager, and signage placed by the contractor, were used to assure proper use.

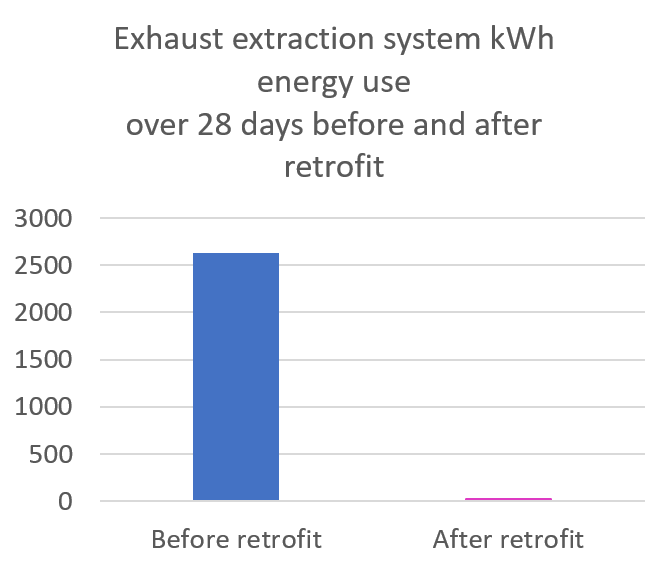

The exhaust fan control retrofit cost $1,200, and over the first month of operation, after the retrofit, energy consumption of the system dropped by 99 percent. Assuming this pattern of use persists, annual savings will total about 34,000 kWh at a value of $3,400 (at $0.10 per kWh), for a simple payback of about four months. This discovery of one easily-implemented efficiency measure was a key success of the project.

It’s no surprise that leaving equipment turned off when it’s not needed can reduce energy consumption. Lots of opportunities stem from this, leading to what some of us at Slipstream call the First Rule of energy use in commercial buildings – that almost every building has one or more energy consuming systems that run excessively. This can result from the absence of controls, a lack of proper programming of automated controls like setback thermostats and building automation systems, and/or a lack of knowledge or discipline by staff in using manual controls.

While the original primary focus of the project was on the accuracy of energy itemization, the project also brought attention to the necessity of engineering knowledge and facility operations information for identifying and planning energy savings projects. Engineering knowledge provides the ability to estimate savings potential for equipment and systems, and operations information provides, for example, operating requirements for each piece of equipment during work hours – the information usually collected in an energy audit. The challenge to energy programs is to bring the right mix of measurement technology, engineering skills, and facility information that enables practical energy efficiency solutions.